With encouragement from Martha, I want to state more precisely the paradox that I think is at at the heart of what we are doing, esp. when we take our best pictures (the ones that so many of you showed last night, that make us go ooh or wow).

What is happening to the way we see the subject and the reality it’s part of when we make it into a subject or story? (This same thing happens, I believe, when we take the picture in the field, choosing what frame and what to blur or focus on; when we are editing it; and when as viewer we are looking at our own or someone else’s image).

Here’s what I think is at the heart of this process:

1. We identify in our mind something that stands out from everything we are looking at. It stands out because it makes some connection to us (something that makes us react to us as being something more and special than its context). We have the sense of that connection, or sense of potential connection, whether we can articulate precisely what it connects to, what it leads to fire within us (this is a way of speaking but also literally in terms of neurons).

This act, this firing, is similar to the much simpler (but still incredibly complex process) by which rods or cones fire, triggered by the registering of a change, in color or motion, that lets us see anything in the first place. Seeing itself even in these most basic ways, as Eric Kandel argues, is not and — because of the incredible amount of information always available — cannot be a passive process, a simple registering of what’s visible. Rather it’s an active process of constructing a visual reality by focusing only on a tiny amount of that information. This visual reality is a construction in and of the mind, not simply what’s ‘there’.

The glimpsing of a subject or potential for a subject (to be more precise) involves far more of the mind including memory, imagination, emotions etc. In fact since our minds are not abstract Cartesian computers but embedded in flesh and blood, emotion is a fundamental element or base in what drives us to glimpse a subject or potential subject; it is at the very base of our reaction.

2. Making something into a subject, both in that initial glimpse and in each of the actions we take from then on to literally make it the subject of a photographic image, involves a paradoxical process that moves in two directions at the same time.

a. We are separating the subject from the unified world it exists in, both in space and time, and making the rest of that world into the subject’s surroundings or background. (This is true whether the subject is closed and simple or as Bob mentioned last night, the subject is the complexity of the demonstration with the police in Buenos Aires. The subject need not be an object — in fact it’s rather the status that object takes on which is precisely what makes it a subject.)

b. It’s an illusion (a simplifying illusion that our photographing draws on and utilizes) that what we see in the world are separate, independent objects; that they can exist in their very form except by virtue of the relationships with everything else. This is true of course of the golden barrel cactus with its needles drawing and pooling drops of water from the atmosphere as Danny so graphically showed us. But it’s equally true of the sandstone rock that Sapna had us look at an image of, a rock shaped and being shaped by the action of water and wind, of people climbing on it, of Indians creating hollows in its surface for grinding acorns. Nothing exists outside its past or present connections with everything else.

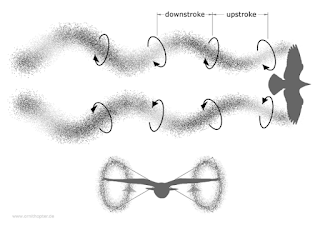

What is really there, whether we see it that way or not, are systems and processes, and relationships between those processes. The photo I showed of the electrons of krypton atoms jumping each 150 billionths of a billionth of a second, in the fastest equivalent to a shutter speed we now have, illustrates precisely this. There are actions and processes, not objects.

c. When we identify and thus, in potentiality, create a possible subject, we utilize this illusion — that this fraction of instant and fraction of space shows us something that is ‘separable’ in this sense. Another way of saying this is that we exclude everything else as ‘background’, whether we let portions of it remain in the frame or not.

d. The strongest photographs are the ones, I’m learning from the class, that — in the word Bob uses so powerfully — that are the purest, that is where the subject or story is the most purely separated from its background and context so that we as the viewer can see and feel its power most intensely.

e. So, when we see and record and share so others can hopefully see the power of that purity we are most making the subject visible as subject. All the steps we take in framing, focusing, setting aperture levels and ISO’s, in editing, in cropping, in changing light levels, and then in looking are all aids in creating and preserving this sense, this status.

f. Yet, what draws us to a subject in the first place, what elicits our reaction that moment when we’re walking around, camera at the ready, and the reaction that we then intensify, share and participate in, is precisely not the isolation of the subject but its connection to thoughts, feelings, sensations that go beyond that subject. What is this ‘beyond’?

When we look at Bob’s photo of the echo of the two birds, one in focus and the other behind it a little blurred, we have a powerful reaction that is what gives the subject the energy it has for us. The image, of this particular moment of time and space, connects us to a sense of replication and duplication in nature, of echoes and rhythms within our own mind, of feelings that draw on many parts of us.

g. Thus in taking these photographs we:

1) identify, frame, intensify and purify a subject by removing it from its actual context (from the moments before or after when those two birds won’t be in that precise physical relationship, from all the space and sights around them, from the world they are part of), and

2) instead, and by this very action, connect it to a broader set of linkages within the mind of the photographer and the viewer.

There is thus a movement away which is part and parcel of this movement toward, from one set of contexts and linkages to another, from a world that is unified to a set of linkages within the mind where subjects and stories exist and glow for us.

3. It’s this double process, this paradox as it were, that I think lies at the heart of the best of what we do in taking effective photographs.

This same process is at work whether a child is taking a snapshot of a friend for Facebook, making that face into a subject, or it’s Cartier-Bresson or Edward Weston distilling a great vision. It’s true in all photographing, even if done seemingly entirely by a machine such as a programmed space telescope or when the images created in that way are evaluated, even if by a machine, to identify differences in the sky the night before. Because there is a human being who is creating and determining the settings of what will be defined as a subject or story.

The more powerful, the purer the photograph, the more successful this double process has been — of making some aspect of visual reality into a subject or story that transcends by excluding it from its surroundings and making it part of a mental-emotional discussion within one person’s mind or a discussion between many, reacting to that photograph.

Because a photograph provides a specific (if highly and valuably partial) visual record, captures the actual light recorded from a specific scene in a specific moment, and makes that record or its results available, it’s easier to see this process at work than when a poet creates a subject out of some scene (Mary Oliver of honking geese) but I expect the same two-way process is at work, both for the creator and each viewer or reader.

That, at least, is how I can best discern what I think is going on after a week of this very excellent class.

I’d love feedback on where you think I’ve gone wrong or that can further push these insights toward deeper truths.

– Gene Slater